Matt Dodwell epées me to pieces. I'm a bit new to the video technology here, but it seems to work better the second time you run it for some reason. Things to look out for when you do: Matt's level shoulders compared to my continually tipping ones; Matt's neat parries of my useless lunges compared to my wild flailing at his feints; Matt's expert touch on my foot to score the point compared to my accusing look at that foot after he has done so.

Fencing Video

Posted by John McClure at 2:52 pm 6 comments

Fencing

Fortunately the mask is very good at stopping you losing an eye.

I lunged. I parried. I feinted. I remised, reprised and reposted. And I lost. Heavily. Three times.

First up was the foil verses Jamie Kenber. They could make getting dressed for fencing an event in itself, but then I suppose it is rather important to do it right for safety’s sake. Suitably togged (and wired) up, I took my guard against the reigning British champion, with Ken, resplendent in blazer and tie, presiding.

“En garde!”… check… “Are you ready?”… are you joking?… “Fence!”…ok, here we g…oh… that’ll be one-nil then will it?

And repeat.

Fifteen times in a row.

The British Champion waits for me to make a false move before striking. He didn't have to wait long.

To say that Jamie Kenber is rather good at foil is like saying that George Best wasn’t bad at football. Fair enough, I suspect any of the rest of the foilists in the room could probably have beaten me 15-0 too, but at least half the times he hit me he did it so fast and so accurately that the sound of the buzzer genuinely surprised me because I hadn’t felt a thing.

Afterwards, as I dismantled my foil outfit and started trying to work out how to put on my sabre gear, while Jamie put on his jeans and started trying to work out what to do with the rest of his evening, he confessed that he wasn’t quite at his best at the moment as he’s carrying a bit of a back injury. All I can say is God help the rest of you foilists when it clears up.

After a quick breather, it was on to the sabre verses Michael Coombes. Having spent pretty much the whole of the first fight like a rabbit trapped in some particularly transfixing headlights, I was determined to get a bit more aggressive in this one. “Fence!” cried Ken. I bounded forward and got slashed on the head for my trouble – time for a rethink.

Michael Coombes's attacks were relentless. So was my failure to do anything about them.

Time and again Michael came at me and I failed utterly to parry his attacks. Time and again as we shuffled back to our marks I did that thing that batsmen and golfers do after a bad shot – I replayed the parry in the air as I would have liked to have done it a moment before and shook my head ruefully. This was a fairly good indicator of how far behind the game my brain was working – I was just about ready to parry the previous attack as the next one began.

Finally, I dug my heels in and remembered the odd fragment that people had worked so hard to teach me over the previous three weeks. I initiated an attack of my own. It was easily parried, and the reposte would have severed my jugular vein had I not been wearing the mask, but it got me thinking that just maybe I might get a point.

With my next attack, I did! As had been the case with most of the other clashes, I’ve really no idea what happened, but the buzzer buzzed and Ken pointed at me and announced that the score was now 10-1 in Michael’s favour. I carried on with my attacking strategy. It didn’t work. I lost 15-1.

By now, I was exhausted, despite having done in total (if you don’t count getting into and out of the gear) about 3 minutes exercise. The layers of protective clothing are very reassuring when someone is waggling a sword at you, but it ain’t half hot under it all.

I stripped down out of the sabre gear and set about dressing for epée. My opponent this time was Matt Dodwell, silver medallist in the British Youth Championships and 3rd ranked junior in the country at the moment. He’s also a good couple of inches taller than me and has a reach like Michael Phelps touching the wall.

Matt Dodwell advances with his big long arms, preparing to stab me in my big fat head.

As I was walking back to the piste Michael, my previous opponent, took me to one side and offered some last minute advice. It was kind of him, and I wish I could have repaid that kindness by remembering what he’d told me before I found myself 7-0 down again. Finally I did remember – “just stick your arm out as far as you can when he attacks and you might get a simultaneous hit” – and did as I had been told. My reward was my second (and last) hit of the night.

In truth, it slightly backfired as a tactic. Much like when Liverpool score early in the Champions League, I couldn’t help but feel like I’d only succeeded in making the opposition cross. With his next attack, he fleched. A fleche is essentially running at your opponent and hitting them on the way past. He later told me it was one of the best ones he’s ever done. The fact that I offered such pitiful resistance perhaps contributed to that.

As Matt reaches in hit me on the foot, I desperately try to parry to avoid him ripping my very attractive socks.

From there on, he pulled out all the stops, hitting me with absolute impunity on the foot, the head, the arm, the chest and the throat. I mostly didn’t have a clue what was going on (that’s true in general, but particularly so whilst fencing), but Ken informed me afterwards that I’d been done very artfully by a real expert.

And so the fencing came to an end. I have enjoyed it thoroughly. I can see why it’s not a more popular spectator sport – it’s too fast to follow unless you’re an expert and you know what to look for – but from behind the mask, it’s very exciting.

I spent most of last night feeling like I was letting down all the people who had given me so much of their time in recent weeks. I felt like everything I’d learnt went out the window the moment Jamie Kenber stabbed me in the chest before I’d even reacted to being told to fence. My teachers had stoked me up with numerous techniques for parrying and attacking, and I’d practiced them at home (La Vache is cut to shreds) until I felt reasonably comfortable doing all of them. In the fights though, it was fairly pointless knowing how to parry a certain attack when my eyes couldn’t move fast enough to see the other guy’s sword most of the time.

But then I got home and watched some of the video footage. Their teaching wasn’t entirely wasted. My feet were quite often in the right place, and occasionally I did manage a parry, not to mention the two glorious points I scored. I was glad to see that my body managed to reproduce some of what I’d learnt, despite my brain’s strongest urging to my legs to turn tail and run.

Ken pulled out all the sartorial stops in his role as president.

Huge thanks to the Oxford University Fencing Club – to Ken for his coaching, presidency and kind donation to Sobell House; to Jamie, Michael and Matt for spending time thrashing a novice; to Alex, Alec and particularly to Ellie for all their coaching and encouragement; and to all the rest of the members for putting up with a duffer taking up one of their pistes all night and for not laughing too much at his efforts.

Also, thanks as ever to the fan-base – to the other Johns, Kev and Tracey for taking the photos, shooting the video and making the sarcastic comments throughout. I’m nothing without you people.

Fencing Results

Foil

Lost to Jamie Kenber, 15-0

Sabre

Lost to Michael Coombes, 15-1

Epée

Lost to Matt Dodwell, 15-1

Posted by John McClure at 4:32 pm 5 comments

Fencing Preview

“The three swords used in fencing competitions are the foil, the epée and the sabre.

The foil has a flexible rectangular blade with a blunt point. Touches may be made with the point on the trunk of the body between the collar and the hipbones.

The epée, the traditional sword of duels, has a rigid triangular blade with a point that is covered by a cone with barbed points. Touches may be made on any part of the body.

The sabre is a flexible triangular blade with a blunt point. Both the point and the cutting edges can be used to score touches, which must be made on the body, above the waist, including the head and arms.

In all events, a wire is attached to the fencer’s sword. This wire runs through the fencer’s outfit to a scoring box. When contact is made on the opponent’s body, a light flashes on and a buzzer sounds to record a hit.

Over the years Olympic fencing tournaments have used a variety of formats incorporating both round-robin pools and double-elimination rounds. The format currently in use is a single-elimination tournament, such as is used in boxing and tennis.

Each match is played to 15. If the score is tied after nine minutes, one minute of sudden-death overtime is contested. Before the final minute, the referee determines, through a coin flip or drawing of lots, which fencer will win should no touch be made in the additional minute.”

[with thanks once again to David Wallechinsky and his wonderful book, The Complete Book of the Olympics]

The history of fencing in the Olympics is rich and dramatic. For all my chuntering on recently about my chances of getting sliced, diced, chopped, skewered, stabbed, slashed, hacked or in any other way run through, I was mostly just trying to make it sound exciting for you and was fairly confident that all the protective gear one has to wear would do its job. Then I made the mistake of doing some light research.

In the games in Moscow in 1980, during the semi-final of the team foil competition, the Soviet world champion Vladimir Lapitsky was accidentally run through the chest when his opponent’s foil broke his leather protective clothing. The sword severed a blood vessel but missed his heart.

In 1982, two years after winning gold in the individual foil competition in Moscow, Soviet Volodymyr Smirnov was fencing West German Matthais Behr in the world championships (which Smirnov held at the time) in Rome. During the fight, Behr’s foil snapped, pierced Smirnov’s mask, penetrated his eyeball and entered his brain. The 28-year-old Smirnov died nine days later.

Almost as bad is the number of times some light-hearted, albeit competitive, swordplay sparked such bad feeling that the protagonists resorted to actual duels in order to settle their differences.

After a dispute in 1924, the Italian-born Hungarian fencing master Italo Santelli, who was 60 years old at the time and coaching the Hungarian foil team, was so insulted by the Italian team’s accusations that he lied to an official in order to get them thrown out of the competition that he challenged Adolfo Contronei, the Italian captain, to a real duel.

They acquired permission from the government to have at it, but before they could meet, Santelli’s 27-year-old son, Giorgio, invoked the code duello and demanded that he fight in his father’s place. They met on the Italian-Hungarian border and fought with heavy sabres. After two minutes, the younger Santelli caught the Italian captain with a blow to the head that left a deep slash. The duel was stopped at that point by doctors who were in attendance.

The same games inspired another duel between an Italian and a Hungarian. This time, the former, Oreste Puliti, was a fencer and the latter, Kovacs, a judge who accused the Italian’s opponents of throwing their fights. Puliti was outraged by the accusations and threatened to cane Kovacs, and was thus promptly disqualified.

Two days later, the pair bumped into each other in a music hall. The Hungarian judge listened to the ranting Italian and then haughtily told him he couldn’t understand a word he had said, as he didn’t speak Italian. Puliti punched him in the face and asked if he had understood that any better.

The men were pulled apart, but a formal duel was proposed. Four months later, this time on the Yugoslav-Hungarian border and accompanied by seconds, swords and spectators, they got stuck in again. After an hour of slashing away at each other, the spectators separated them having grown concerned about the severity of their collective wounds. Their honour restored, the two men shook what was left of their hands and made up.

In fact, looking through the history of the Olympic fencing events, the only possibly useful tip I picked up came from the 1928 Amsterdam games. Frenchman Lucien Gaudin became one of only two people ever to have won both the individual foil and epée gold medals. His countryman and opponent in the final of the epée, Georges Buchard, later claimed that Gaudin had begged and pleaded with him to allow Gaudin to win their match – so much so that Buchard agreed to do so.

As for my opponents for Thursday night, I’ve only really met one of them.

Matt Dodwell fights epée, is the current British junior number 3 and won the silver medal in the British Youths Championships this year. He is left-handed. While this will make him more difficult to fence, I have the consolation that it will apparently “look better in the photographs”. I watched him briefly last week as he fenced Alec (who later put me through my paces). I’d love to be able to say that I spotted a weakness that I intend to exploit – other than a curious leaning towards a pint of cider rather than stout in the pub afterwards, he seemed a perfectly balanced individual - but the truth is that I’m not even good enough at fencing to realise what makes other people good. That said, I suspect the fact that he’s comfortably taller than me and has fenced at various levels for his country might just give him an edge.

I also watched Michael Coombes fence sabre last week. Michael was 3rd in the Public Schools Senior Boys Sabre Championships this year. Even with Alex telling me exactly what was going on as each touch was scored or missed, all I was seeing was a frantic mêlée of arms, swords and feet that every so often would stop when the scoring box would buzz for no reason I could discern. It got me wondering if perhaps this is the reason fencing is not a more popular event at the Olympics - I was fairly avidly glued to the TV for the duration of the last games, but I’m not sure that I saw even an edited highlight – perhaps the technicality of it all requires a higher understanding or intimate knowledge of the sport on the viewer’s part than is generally the case in order to appreciate what’s going on.

There are rules of priority that are hard to bear in mind when your mind is already full of where your feet should be or how bent your elbow is. These rules essentially mean that on some occasions, while it may look like one fencer has scored a clear hit, it is in fact the other swordsman who gets the point. As a beginner, after a while, it can begin to feel a little like a sport someone is making up the rules of as you go along in order to make sure you don’t win.

The only thing I did notice about Michael’s style that may be helpful was that he likes to move forward – then again, perhaps the chap he was fighting simply likes to retreat – either way, I’m going to adopt a tactic of running at him as fast as I can to see if I can upset his natural game. This tactic might rank up there for stupidity alongside my long held game plan should I ever find myself playing snooker against Ronnie O’Sullivan to hit the balls all over the table and disrupt the patterns he’s used to playing within.

My foil opponent is Jamie Kenber. I’m almost sure I’ve seen someone at the fencing club with that name on his back at least once, but I can’t bring his style to mind. All I really know about him is that he is ranked ninth in the senior British rankings and is the current British foil champion. In the final he beat one Richard Kruse, who fought for Britain in the Athens games. I made the mistake of looking in the Team GB official Olympic report tonight to see how Mr Kruse had done. He got to the quarterfinals, which by my (perhaps skewed) reckoning makes him one of the best eight foilists in the world. He lost out to the man who eventually took the bronze medal.

His performance was the best by a British fencer with any weapon since 1964 when Henry Hoskyns, a 33-year-old fruit farmer from Somerset, finished seventh in the foil and won the silver medal in the epée. Kruse's achievements were all the more impressive given that he had only recently graduated from university and was fighting professional opponents with superior back-up and training facilities. And then he came home and Jamie beat him. And now I have to fight Jamie. So that should be easy.

Perhaps I’ll try some of that begging and pleading after all.

Posted by John McClure at 11:38 pm 11 comments

Strictly Come Fencing

I have a confession to make. Anyone who knows me and has had the misfortune to find themselves on the dance floor when I take a notion to strut my stuff will be aware that I’m not a fan of conventional dancing. You can keep your regimented steps and synchronised movements; I’m usually the one in the middle annoying everyone with the randomness of my gangly gesticulations. This lack of fanaticism for all things Fred Astaire extends to watching other people indulging in such activity – Strictly Come Dancing? Strictly No Thank You.

And yet, perhaps worse than tuning in on a Saturday night to watch seasoned professional ballroom dancers guide gormless celebrities through a quickstep or a jive in an attempt to survive the dreaded public vote, I’ve caught myself several times this week not changing the channel when the nightly magazine programme that accompanies the weekly series appears on my television.

Strictly Come Dancing – It Takes Two (for that is what it is called) tracks the trials and tribulations of the clueless amateurs as the professionals try to teach them a new dance in preparation for the following week. Tonight, I caught myself watching it again and also noticed that I have been doing so rather more than someone with no interest in that sort of thing ought to – and certainly rather more than someone who has never watched the actual programme proper.

I’ll admit to having a slight soft-spot for the host, Claudia Winkleman, and that her penchant for a plunging neckline has done little to make me want to switch channels and watch ITN butcher the day’s news, but there’s something deeper going on. As I sit here writing with the show on in the background, I should instead be dancing up and down the living room wielding a sabre and attacking an ironing board. The reason I’m not practicing my fencing as I should be is that I’m enjoying watching other people going from a position of being all at sea to dancing a waltz as though they’ve been doing it for years.

Just now, I nodded with rueful recognition when Zoë Ball confessed to messing up her foxtrot because she forgot which foot she was supposed to start on. I felt Goughie’s pain when he grimaced with frustration at not being able to do the five things he’d been told to do all at the same time.

In an hour, I’m heading off for my last training session with the fencers before they slice and dice me in the three fights next week. Learning is repetition. If you’re the pupil, you do something wrong in a slightly different way over and over and over again until you get it right. Then you do it wrong again and swear a lot because, damn it, you had it mastered a minute ago!

If you’re the teacher, you tell the pupil the same thing in a slightly different way over and over and over again until something clicks and he gets it right. You commend him far too much for finally doing what you told him to do in the first place, and then you laugh at him when he messes it up again and gets cross.

I’ve said before, but will say again, that I greatly admire the patience being displayed by the people trying to teach me; it outlasts my own without fail and by a long, long way. The one thing I am learning better than anything else is that learning itself is much easier to do when you’re a child and repetition (as you will no doubt know if you have ever encountered a child who is asking for something) is just about your favourite thing in the world.

UPDATE:

Jamie Kenber (foil) is the current British Men's champion, beating British Olympian Richard Kruse in the final this year. He is currently ranked 9th in the senior rankings.

Matt Dodwell (epée) is current British Junior No.3 and was the silver medallist in the British Youth Championships this year. He is currently ranked 21st in the senior rankings.

Michael Coombes (sabre) was 3rd in the Public Schools Senior Boys Championships this year.

All three are members of the University of Oxford first team.

You can think of them as the three musketeers. I shall be thinking of them as the three guys who have very kindly offered to come along and chop me into little pieces next week.

Posted by John McClure at 7:39 pm 7 comments

Different Strokes

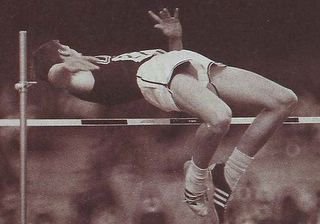

What a different place he world of high jump would be had Dick Fosbury not thought of having a go at it backwards.

I’m a dreamer. I’m reliably informed by John Lennon that I’m not the only one, but still, that’s what I am. One recurring daydream that started shortly after I came upon the notion of doing all this involves discovering that far from being blunderingly inept at all things Olympic, there might just be an event that I’ve never tried before but turn out to be astoundingly good at.

In idle moments I imagine the Great Britain pole vault coach scratching his head and looking at a clipboard as I fall back to earth having cleared the bar by a foot. He is confused and exclaiming “But… that’s a British record. By half a metre. You’re in the team for Beijing.”

I confessed this dreaming habit just now to my colleague and friend Statue John while we smoked very un-Olympic cigarettes in the alleyway beside our office. He confessed in his turn that he has spent many idle hours thinking about “doing a Fosbury” – coming up with a revolutionary technique for performing one of the events that ensures victory despite a lack of what is commonly held to be the usual physical requirements of an Olympic champion.

At the 1968 games Fosbury revolutionized the sport of high jumping with just such a new technique, which became known as the Fosbury Flop. Instead of leaping facing the bar and swinging first one leg and then the other over the bar in a scissoring motion - the dominant method of the time - Fosbury turned just as he leapt, flinging his body backward over the bar with his back arched, following with his legs and landing on his shoulders.

The best John and I could come up with was some new swimming technique that would allow you to win the 50m Freestyle despite having a massive beer gut, baggy swimming trunks and (John insisted) a lengthy mullet unrestrained by anything so naff as a swimming cap.

Certain events heavily regulate techniques – for instance, I’m fairly sure that John’s suggested new long jump technique involving landing headfirst and rolling forwards (anyone who has seen the A-Team will know that such a technique can carry a man far enough to land a safe distance from and exploding jeep) would not only result in a concussion but also be against the rules of the event.

But others (like freestyle swimming and most of the track events) just involve covering a set distance as quickly as possible. Michael Johnson has a fair claim to being one of the greatest track athletes of all time, and he modelled his running style on that of an ostrich. His coaches told him it wouldn’t work, but he refused to listen (his training partners had to tell him he had gone a bit far when he started burying his head in the long jump pit mind you).

So rack your brain, loyal reader, and post a suggestion – be it pole-vaulting with a pole twice as long as the ones the experts use, or paying homage to Dick Fosbury by running the hundred metres backwards – all suggestions will be heard. And then roundly mocked, no doubt.

Posted by John McClure at 5:28 pm 10 comments

On Guard!

In between fights, fencers like to get together and practice their high jump technique.

Fencing is one of only four sports to have been included in all of the modern Olympic games. It’s also one of those things that every man who never really grew out of being a little boy would really rather like to good at. Whether you fancied yourself as Errol Flynn’s Robin Hood, Oliver Reid’s Athos, or (in my case) Guy Williams’ Zorro, sword fighting was something no young boy with access to a couple of sticks and a willing accomplice could resist.

Thanks (once again) to Kev Game and his remarkable ability to pull strings, I found myself last night in the Cricket Schools at the university sports centre, surrounded by sword-wielding experts dressed up like svelte bee-keepers. I was looking for Ellie, the kind soul who has offered to teach me the foil (one of the three fencing disciplines – the other two being epée and sabre).

Our plan, hatched by e-mail, had involved me coming along to a practice session and being put through my paces. It was a good plan, ruined only by my latest embarrassing injury. It was bad enough making it through forty arduous, high-speed kilometres of cycling in the triathlon without so much as a wobble only to come crashing to the ground a few weeks later cycling to the shops one Sunday evening, but this time, I may have outdone myself.

I’ve had a bit of a cough for a few days (I’m no doctor, but I suspect that walking home from a nightclub at five in the morning with my shirt open to the waist may have had something to do with it). The cough was just beginning to subside, but it was determined not to go without a fight. During one particularly violent outburst, I somehow managed to strain a muscle in my right side. It’s a tiny muscle – one I didn’t even know I had – but one that seems to be fairly heavily involved in just about every movement I try to make.

Fortunately for me (and my aching side), the first steps in learning to fence would seem to be just that – steps. Having found Ellie and marvelled at how much consideration she seems to have given my quest (“We’ll try to get you fighting left-handers if we can. It’s harder, but it will look much better in the photographs.”), I was introduced to Alex, a sabre specialist, who took me through some footwork.

One of the toughest things about this whole challenge is learning how to do new things. I don’t yet consider myself an old dog, but I do seem to struggle with the learning of new tricks. When I first started giving some serious thought to the challenges I would face in trying to have a go at all the Olympic events, I expected a lack of fitness to be by far the largest obstacle to my completion of most of them. Naively, it didn’t really occur to me that a lack of talent would also be a problem.

As I stumbled backwards and forwards trying to keep my distance from the young lady pointing a sword at my head and reminding me (very patiently) to keep my shoulders level, I suspect I looked more like a man caught up in his first barn dance than Errol Flynn toying with the Sheriff of Nottingham.

I am lucky to have once been good enough at a golf that the odd beginner occasionally asked me for advice. I would do my best to offer it patiently and politely (in the manner it had always been offered to me), but I was constantly fighting the urge to bellow, “Oh for God’s sake, just hit the bloody thing!” As such, I have unending admiration for everyone who has thus far offered me coaching (in any discipline) and managed to resist bellowing the same thing at me. Alex and Ellie are two more such people to add to the list.

Once Alex had finished teaching me how to dance up and down the piste, and even run me through (a poor choice of expression perhaps) how to go about striking my opponent with a sabre, she passed me back to Ellie who introduced me to the foil.

As it turns out, there are five different guards one could adopt when fighting sabre, but Alex must have realised fairly quickly what level she was pitching at and just taught me the easiest one. Ellie had no intention of letting me off so lightly with the foil and was quickly talking me through the nuances of sixte, quarte, septime and octave. Luckily, she also sent me home with a book full of pictures to jog my memory.

If the helmet masked my puzzled expression, I suspect my teacher quickly revised the detail of her teaching plan when we started talking about instincts. Having told me that essentially every movement in fencing is “instinct refined and honed”, she tried to demonstrate her point my slowly lunging towards my left side.

“What would your instinct tell you to do there?” she asked.

“Well – to move my sword across my body and deflect your sword.”

“Very good! Then what?”

“Then I’d probably reach over and punch you in the face with my other hand and wait for a fellow musketeer to break a chair over your back.”

Despite my cavalier attitude, we hatched a new plan, the broad (if optimistic) aim of which is to get me through all three fencing disciplines before the student body disappears at the end of Michaelmas Term (so the beginning of December). They have their work cut out, but they sent me home with a helmet and a sabre so that I could get some practice in at home as my side improves. As such, I take great pleasure in introducing you to my new practice partner. I think I’ll call him ‘La Vache’.

He may not look up to much, but the horns really freak me out.

In the eyes of the law, a sabre is considered a deadly weapon, and therefore not for carrying on the bus. Amazingly though, everyone was in agreement that the act of shoving half the blade into my umbrella was enough to render it legal and I set off for home with a helmet under my arm and a Bank of Scotland umbrella-sword at my side. I’m not so grown up that I won’t confess a certain feeling of satisfaction at paying my bus fare with a ten-pound note despite having change in my pocket. For once, the driver didn’t ask me if I had anything smaller.

Posted by John McClure at 3:13 pm 12 comments